Our Town - Hastings and St. Leonards

Location

The town of Hastings lies on the Sussex coast in the south-east of England. The historic “old town” of Hastings nestles in the valley between two hills, with the modern town to the west of them. The town of St. Leonards-on-sea, founded in the 19th century to the west of Hastings, has grown to the point where the two towns are now contiguous and form part of one combined borough.

Hastings is where the A 21 road from London jons the A259 coast road that runs the length of Sussex from Chichester in the west through Brighton Eastbourne and Hastings, and eastwards to Rye and into Kent and the English Channel port of Folkestone.

Trains go east to Rye, then on to Ashford. To the west, the railway goes along the coast to Bexhill, Eastbourne, Lewes and Brighton. For London, the most direct route is the Charing Cross service which takes about 1 hour 45 minutes, going through Battle and Tunbridge Wells. There is also an alternative London service going west to Lewes and then north via Gatwick to Victoria. As well as the main Hastings rail station there is a smaller one called Ore to the east on the Ashford line, and there are two stations in St. Leonards-on-sea: Warrior Square, in the heart of St. Leonards served by all the trains, and West St. Leonards which is for trains on the Charing Cross line only.

History

“Hastings” means, literally, the sons or dependents of “Haest”, and the town seems to have been founded by a chieftain of this name, or by his followers. It seems to have been a more-or-less self-governing enclave within what was then the Saxon kingdom of Sussex, during the “dark ages” of Britain. This has suggested to some scholars that Haest and his followers were probably not Saxons like their neighbours, but may have been perhaps a Danish or Jutish people.

The town is best known because of the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Duke William of Normandy invaded Sussex and, having seized and pretty much destroyed the fishing village of Hastings, quickly erected a make-shift wooden fort out of prefabricated parts that he had brought with him from Normandy. The English King Harold and his army were in the north of England at this time, and William being unopposed started laying waste to the country around, possibly to provoke Harold into a premature attack. If so, the tactic succeeded. After a forced march of several hundred miles, Harold’s army confronted the Normans at the Battle of Hastings on 14th October, and lost. Harold himself was killed along with his two brothers. Although pockets of resistance to the invaders remained, effectively it was over. On Christmas day 1066 William was crowned king of England.

The effects on England of the Norman conquest were cataclysmic. Unlike other famous battles such as Agincourt or Waterloo - which though spectacular did not really have any long lasting effects - the Battle of Hastings really did alter the whole course of our history. It is fascinating to speculate what would have happened if Harold had won: it was after all no easy victory for the Normans, and the result could well have gone the other way. The Normans stamped the sign of their victory upon the town of Hastings in the form of the stone castle, replacing their original wooden one, whose ruins can still be seen and visited on the West Hill today.

The actual site of the battle was traditionally thought to be located some eight miles inland from Hastings, on the hill where the Normans built an Abbey to celebrate their victory, around which grew the town now called Battle. However this theory has been called into question. A local historian John Grehan has made out a case for suggesting that the battle actually took place a mile away from the Abbey at Caldbec Hill, on the other side of Battle town, while another investigator Nicholas Austin has put forward an even more radical proposal, suggesting that the battle took place just outside Hastings itself, near the present day village of Crowhurst. The jury is still out on this controversy, but it does seem odd that no relics of the battle, or of the many soldiers who were killed, have ever been found on the slopes of Battle Abbey.

Hastings flourished during the Middle Ages as one of the leading members of the Cinque Ports confederation – a group of towns along the south-east coast that were granted special privileges by the King in return for providing and manning ships when needed – usually for fighting against the French. Of course its location on the south coast made it an easy target for French raiders. After King Edward III started the “hundred years war” the French attacked and burnt the town twice, once in 1339 and again in 1377 (thanks a bunch, Edward!) However after the silting up of Hastings harbour, and the conquest of Normandy by France, Hastings was of little further use as a port. The town returned to being a modest fishing community with a lively sideline in smuggling, until the fashion for sea bathing at coastal resorts gave Hastings a new lease of life in the 18th century.

One side-effect of this was the planning and building of a new town just to the west of Hastings by the architect James Burton. It was called St. Leonards-on-sea, and included some impressive features such as the Maze Hill Gardens and Warrior Square. As both towns continued to grow however they filled up the space between them, and merged effectively into one – although even today there are still noticeable differences in the “feel” of the two communities.

The writer Sheila Kaye-Smith was actually born in St. Leonards, and her novel “Tamarisk Town” published in 1919 is set in a thinly-disguised Hastings under the name of “Marlingate” and describes how the town was transformed from a somewhat moribund fishing community into a fashionable seaside resort.

This was not the first time that Hastings had appeared under a pseudonym in a work of fiction. There is a fascinating “snapshot” of Hastings in the early years of the 20th century in the pages of “The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists” by Robert Tressell, the pen-name of a decorator and sign-writer called Robert Noonan who lived and worked here for a while. Under the name of “Mugsborough” the Hastings of the Edwardian era is described from the viewpoint of the depressed and chronically hard-up workers in the decorating trade that Noonan knew so well, in the days before there was any such thing as “unfair dismissal” or social security.

One of Robert Noonan’s contemporaries in Hastings was the celebrated French Jesuit philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who lived here from 1908 to 1912. His experience of Hastings was very different from Noonan’s however! Teilhard spent his time here studying theology and in 1911 was ordained into the Catholic priesthood. Shortly afterwards Teilhard – a keen proponent of Darwinism – became involved in the notorious “Piltdown Man” fraud, although it has never been proved that Teilhard himself knew about the deception. Teilhard’s ordination into the priesthood took place in the Catholic church of St Mary Star of the Sea, which you will find at the northern end of the High Street in the Old Town. This church has its own interesting story: it had been built in the mid 19th century from funds provided by the once-fashionable poet Coventry Patmore as a memorial to his deceased wife. It was at this church too that the writer Catherine Cookson, who lived and worked in Hastings from 1930 until 1976, was married in 1940 to local maths teacher Thomas, who is fondly remembered by generations of former pupils of Hastings Grammar School.

Hastings had another brief moment in the spotlight of history in 1923 when at the age of 35 the Scottish inventor John Logie Baird came to stay on medical advice, hoping that the sea air would be good for his health, which was always poor. Having tried and failed to earn a living at assorted ventures which included making insulated socks in Glasgow and jam in Trinidad, it was in Hastings that he made the breakthrough that would immortalise his name: the invention of television, which he developed in his hired laboratory rooms in Queens Arcade, and was first demonstrated to a group of journalists in his bedroom in Linton Crescent.

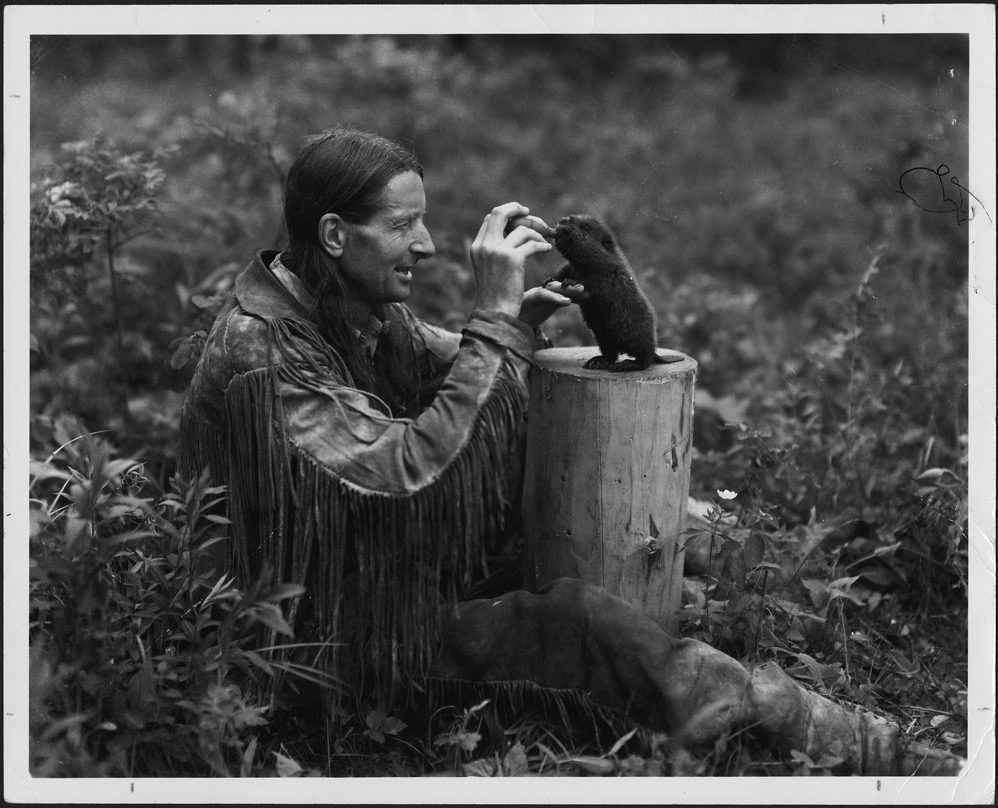

At about the same time, one of Hastings most famous sons was making a name for himself on the other side of the world. Archibald Belaney was born in Hastings in 1888 – making him the same age as Baird, as it happens – and was educated at Hastings Grammar School. His greatest wish was to live the life of an American Indian – and as soon as he was old enough, he ran away to Canada and became one!

Having experienced at first hand the beauty and grandeur of the Canadian wilderness, he was one of the first to realise the implications of the destruction of the forests for commercial gain and the insidious spread of roads and cities everywhere, and he became in effect one of the earliest “conservationists”. Using the pen-name “Grey Owl” he wrote passionately in defence of the wilderness and its creatures. His true identity only became public knowledge after his early death in 1938. It is well worth reading about his extraordinary life and adventures in his own words, in the books “Pilgrims of the Wild” and “Tales of an Empty Cabin”. Richard Attenborough’s film “Grey Owl”, starring Pierce Brosnan in the title role, tells a small part of his fascinating story.

John Logie Baird on the other hand survived until 1946. During the final two years of his life he chose to live in the neighbouring town of Bexhill where he died. About the same time, the notorious occultist Aleister Crowley chose to spend his final years in Hastings, where he lived for three years in a boarding house until his death in 1947. Crowley was actually an accomplished mountaineer and chess player, but chose to devote his life to drugs and black magic. The national press dubbed him “the wickedest man in the world” and when he died the local Council refused to allow his remains to be buried in the town!

The popular childrens' writer Malcolm Saville was born in Hastings in 1901 and also died here in 1982. He is particularly remembered for his series of books about the members of the “Lone Pine Club” which introduced generations of young readers to the beauty of the Shropshire landscape in the west of England, but some books in the series were also set in the nearby ancient and picturesque town of Rye.

The science fiction and fantasy writer Christopher Priest lived in Hastings for some 20 years and Hastings features briefly in his 1995 novel “The Prestige” which was later made into a film by Christopher Nolan. His wife Nina Allen who is also a writer, set part of her 2014 novel “The Race” in the town and readers will recognise many of the streets and local features referred to in the story. Another fantasy writer Tanith Lee lived in the Hollington area of St. Leonards-on-sea until her death in 2015. She remains the only female writer to date to have won the British Fantasy Award. Another fantasy writer now living in Hastings is American-born Leigh Kennedy, whose output though relatively small is quite unique and well worth tracking down.

The White Rock Theatre which stands opposite the pier, originally called the “White Rock Pavilion” dates from 1927 and owing to its superb acoustics it was used as a recording studio by Decca for several years, and attracted many famous classical artists during the 1930s including the pianist and composer Sergei Rachmaninov and conductors such as Thomas Becham and Adrian Boult.

Two important folk musicians were also born in Hastings in the 1930s: sisters Dorothy and Shirley Collins, whose ground-breaking 1969 album “Anthems in Eden” remains a landmark in English folk music. Shirley Collins still lives in Sussex, though Dolly sadly passed away in 1995. In the 1970s the blues singer and guitarist John Martyn lived in Hastings, and it was here that he created what is probably his best known album, “Solid Air”. In addition two top-flight folk fiddlers, Peter Knight (of “Steeleye Span”) and Barry Dransfield both lived in Hastings for many years. Peter Knight still tours with his band “Gigspanner” which includes Hastings musician Roger Flack while Barry Dransfield’s output from his Hastings years includes tributes to the local fishermen in the songs “Haul Away” and the ever-popular session favourite “I once was a fisherman”.

The town is also home to saxophonist Wesley Magoogan, who played with everybody who was anybody on the pop scene until an unfortunate accident injured his hand so that he could no longer perform. However you can hear him at his best doing his celebrated saxophone break in Hazel O’Connor’s song “Will You”. A native Hastings musician who still lives in the town is Steve Kinch, who has been the regular bass player with Manfred Mann’s Earthband since 1985.

Hastings today

Today Hastings has a population of something over 80,000 and depends heavily on tourism to earn its living. Hastings never quite achieved the prosperity of resorts like Bournemouth or Brighton, but it has a comfortable, “lived in” feel and a lot to recommend it which is not perhaps obvious to the casual visitor, such as Alexandra Park: a delightful gem situated just a short way from the town centre. Its streams and small ponds are home to ducks and moorhens. If you are lucky you might also see a cormorant or a heron. Just south of Buckshole reservoir the miniature steam railway offers rides at weekends and on school holidays. The café by the bandstand provides a welcome opportunity to relax with a drink or a meal, either inside or outdoors on the decking, depending on the weather! Adjacent to the rose garden nearby is the “peace garden” entered through attractive wrought-iron swinging gates, and there you will see a bench designed by Alan Wright and installed by the local Quakers in 2015 to mark the centenary of the First World War.

Another easily-overlooked attraction is the remarkable museum and art gallery in Cambridge Road, half a mile up the hill from the town centre. Entry is free, and inside there are some remarkable collections of artefacts from the far east and also from American Indian culture – including of course a special feature on Hastings’ own pseudo-Indian, Grey Owl (see above). Also in the museum is a model of John Logie Baird’s first television apparatus. Interestingly, one of the co-founders of the museum back in 1889 was the solicitor Charles Dawson, the notorious “Piltdown Man” forger, who had lived for much of his childhood in Hastings.

Being a traditional seaside resort of course Hastings has a pier, dating from Victorian times. This local icon however has had a chequered history. Closed to the public in 2008 due to fears about its safety, it was extensively damaged by fire two years later. However due to massive public support it rose from the ashes – literally! – and reopened in 2016. If you are shopping in the town centre, don’t miss the charming Victorian-built Queens Arcade, just off Queens Road next to the cinema where the inventor John Logie Baird rented an apartment to carry out his early experiments on television, before the landlord turned him out for causing explosions!

Down on the sea front, heading east towards the Old Town you will see Pelham Crescent and its centrepiece St. Mary-in-the-Castle, with its magnificent Georgian columns and soaring dome. On the West Hill above, the ruins of the Norman castle are a major attraction as are St. Clement’s caves nearby. For those who enjoy walking in the countryside, the unspoiled Country Park stretches from the East Hill up and down the glens and over the “fire hills” to Fairlight – and further if you can manage it. On the way you can visit “North’s Seat”, the highest point in Hastings, which was named in honour of a long-serving 19th century Member of Parliament for the town, Frederick North. His daughter Marianne North, born in Hastings in 1830, became a famous botanist and illustrator who travelled much of the world in search of her subjects – very unusual for a single woman at the time. Her portrait appears on the outside wall of the Imperial pub in Queens Road.

The Old Town, nestling between the East and West Hills, is well worth exploring: as well as the picturesque houses and shops, the streets are riddled with a surprising network of little alleyways (or “twittens” as we call them in Hastings!) while the beach at The Stade is home to the largest shore-based fishing fleet in England. At the eastern end of the Old Town going past “Winkle Island” with Leigh Dyer’s eye-catching sculpture of a huge winkle in shining metal, you can go down the street called “Rock-a-Nore” past the iconic tall, dark wooden “net shops” to find the famous Hastings fishmarket, where you can buy freshly-landed local fish from the wooden cabins to be found both in Rock-a-Nore itself and also along the walkway that runs parallel to it, at the edge of the beach: much better than buying pre-packaged fish from chain-store supermarkets!

There are lots of great places to eat and drink in Hastings. The popular pub-restaurant “Pissarros” is in South Terrace, just a few yards from the Quaker Meeting House. Inside there is a wall covered in the signatures of various musicians who have been there – including the members of the folk supergroup Fairport Convention. In Waldegrave Street just around the corner from the Quaker Meeting House the curiously-named “Eel and Bear” has a marvellous range of English, Belgian and German beers.

In Robertson Street in the town centre, there are a number of good cafés, then turning into Trinity Street there is the valuable local organic food co-operative “Trinity Wholefoods”. Just around the corner in Claremont it is worth discovering the “Cheese-on-sea” shop with an extensive range of unusual English cheeses. Further on as you reach the sea front there is the excellent Indian restaurant “Ocean Spice”. Continuing westwards, opposite the pier and next to the White Rock Theatre, the White Rock Hotel always has some interesting “real ales” and an attractive food menu,

Heading in the other direction, going east along the sea front takes you to the iconic Old Town of Hastings. Arriving in George Street, first you will see The Albion public house, offering a good selection of real ales and ciders as well as good food and a lively music scene. George Street also offers many friendly cafes and restaurants. At the end of George Street turn left into the High Street to find Judges Bakery, which featured in The Independent newspaper’s 2006 guide to the top 50 food stores in Britain. Various kinds of organic bread are freshly baked on the premises each day, and they also have a wide selection of other organic food and drink. Right next to Judges, don’t miss the wonderful Penbuckles cheese and wine shop, specialising in local produce. Almost opposite is the popular Jenny Lind pub, with an impressive array of real ales and a regular schedule of live music. Heading further up the High Street near to the northern end you will find the charming “First In Last Out” public house which serves good food and good beer – including their very own brew.

Entertainment in Hastings can be found at the White Rock Theatre just opposite the pier, the Odeon cinema in the town centre, and for less “commercial” films the smaller “Electric Palace” cinema in the old town’s High Street, which in 2008 was named by The Guardian newspaper as one of the top ten independent cinemas in Britain.

There is also a remarkable amount of creative talent in the town: artists, writers and musicians seem to be particularly attracted here. Local bands and performers can be heard pretty well every night of the week in one place or another. A jazz club meets weekly on Thursday evenings in the NUR restaurant in Robertson Street in the town centre.

Festivals of every sort abound in Hastings, beginning with the 5 – day long musical extravaganza in mid-February we call “Fat Tuesday” (which is of course simply the English translation of “mardi gras”) which takes place in numerous venues all over the Old Town and in St. Leonards. This is quickly followed by a major cultural event, the Hastings international piano concerto competition, held over several days from late February to early March at the White Rock Theatre, attracting talented young pianists from all over the world. This runs in parallel with the Hastings Musical Festival which is more for local people to strut their stuff, and encompasses all manner of performing arts.

Watch out for the morris-dancing festival of “Jack in the Green” over the early May bank holiday, and “Pirates’ Day” in July which is basically an excuse for dressing up pirate-fashion and having a good time. With the autumn comes the weekend-long “Seafood and wine” festival in mid-September, the Hastings Bonfire with its magnificent fireworks display on the Saturday closest to 14th October (battle of Hastings day!) and in November the Herring Fair celebrating Hastings heritage of fishing as well as other locally produced food and drink. Finally for 10 days over the New Year period the prestigious Hastings International Chess Congress, which attracts the best players in the world – past winners have included Boris Spassky and Anatoly Karpov.

Turning to St. Leonards, the streets at the heart of Richard Burton’s original town are worth exploring. Particularly striking is the Marina Court building on the sea-front, constructed to resemble the shape of an ocean liner! At the ground level is an eclectic mix of shops, art galleries and cafes. London Road, Kings Road, Norman Road, and Grand Parade on the sea front are places where small shops, cafes and family-run restaurants appear able to thrive, in spite of the prevalence of chain-store commercial empires in the Hastings shopping centre.

St. Leonards has plenty to offer by way of entertainment. In Norman Road there is the “Kino-Teatra”, a cinema which also houses a bar and a restaurant. July sees the lively weekend-long St. Leonards festival based in Warrior Square gardens, and on the last Saturday on November there is the colourful and energetic “Frost Fair”, a recent revival of an ancient European tradition.

Along with – perhaps because of – their vigorous artistic communities, Hastings and St. Leonards both have a distinctly “Bohemian” and somewhat radical undercurrent. One eminent Hastings resident is Andrea Needham, who made headlines in 1996 when she and two other women broke into a British Aerospace factory in Lancashire and took a hammer to a Hawk attack fighter plane which John Major’s government was going to sell to the government of Indonesia – which at that time was carrying out massacres of the population of East Timor. The women were put on trial at Liverpool Crown Court for damaging the plane but were sensationally acquitted by the jury on the grounds that they had acted in order to prevent a crime. Neither John Major nor anyone from the Indonesian government or military were ever arrested for the murder of over 18,000 East Timorese.

St. Leonards meanwhile is home to the peace activists Maya Evans and Milan Rai, who made legal history in October 2005 when they became the first people to be convicted under the notorious Serious Organised Crime & Police Act 2005 for the crime of holding a political demonstration in Parliament Square in London, by reading out the names of those (on both sides) who had died in the invasion of Iraq. Merry England!

©Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.